‘It's a Real Crapshoot’: Woman with Serious Illness Needs a Financial Plan for the Best — and Worst — of Outcomes

Trish, 45 and self-employed, has been diagnosed with cancer and wants to make sense of the personal and financial challenges of her indefinite prognosis poses

Andrew Allentuck

Situation: Woman in mid-life has been diagnosed with a cancer that may be mild or aggressive

Solution: Raise cash and investment returns for expectation of long life, but prepare for the worst

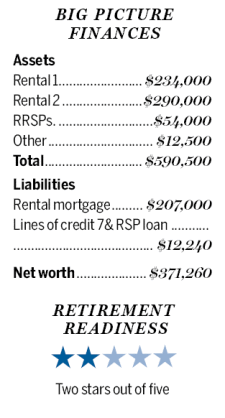

In Ontario, a woman we’ll call Trish, 45, faces a tough choice. A self-employed management consultant, she has been diagnosed with a cancer with two divergent outcomes: It could remain manageable and not interfere with her normal life expectancy, or it could manifest itself and shorten her life expectancy drastically. In the former case, her present $371,260 net worth would need to grow very substantially for a conventional retirement. In the latter case, it would probably be sufficient for a few years of rest before her premature death.

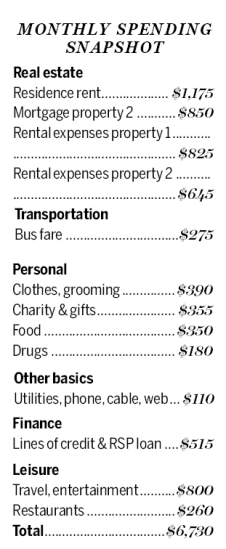

Her indefinite prognosis is a personal challenge and a financial issue she wants rationalized. She has choices, for her present gross income from her self-employment, $5,833 a month, and $500 from two rental properties, total $6,333 a month after expenses for tax, insurance and utilities, more or less allowing her to break even on allocations of $6,730.

The $397 shortfall includes $300 for a line of credit she has used for business. The overrun is not serious, for the business interest cost is tax deductible and helping to generate future income.

Family Finance asked Derek Moran, head of Smarter Financial Planning Ltd. in Kelowna, B.C., to work with Trish. “We have to plan for her to live to a ripe old age,†he explains.

But the dilemma of moving from making do for now to preparing for an indefinite future has to be addressed.

“It is a real crapshoot,†Trish says. “I may die with this disease never having grown into something that affects my ability to earn or it may manifest itself soon.â€

Raising Cash

Trish rents her own accommodation, but owns two rental properties as well.

Property 1, a $234,000 unit in a large building, was her former residence. It has no debt. The sale of the building will force the sale of her apartment. It will create a capital gains tax liability. She paid $162,500 but added improvements worth $30,000, so her cost base is $192,500. Using the formula for capital gains adjustment which recognizes past use as a principal residence, she can take off two years of her own occupancy plus one (as the formula allows) divided by years of ownership. Her tax bill after selling costs will be about $7,000, Moran estimates. She should net about $223,000.

Property 2 has a market value of $290,000. It has a $207,000 mortgage with a 29-year remaining amortization with a 2.59 per cent interest rate. The present rental income is $1,272 per month or $15,264 a year. Her equity is the value less the debt, net $83,000. Her annual return on equity is thus $15,264 divided by $83,000 or 18 per cent. That is a handsome return and the property is well worth keeping, Moran concludes.

She should put some of her capital gain on sale of property 1 into her RRSP in order to lower her income to the top of the first federal tax bracket, $45,916 for 2017. If she contributes $34,084 to her available space, $107,041, she will get a 30 per cent refund.

Next, Trish should pay off $12,240 in credit lines and her RRSP loan. She will eliminate payments of $515 a month.

Then Trish should open and fund a TFSA using the cash remaining. That will use her present $51,000 available space in full.

Given her health issues, Trish should have a hefty emergency fund to cover three to six months of expenses. She can use some of the remaining cash from the property. If she puts six months’ expenses, about $40,000, into a so-called high interest bank or credit union account, she will still have about $96,000 left for investment.

This money, if invested in shares of banks, telcos or utilities that pay 3.5 per cent to 5 per cent would generate between $3,350 and $4,800 a year on top of what could be asset price growth of a few per cent per year.

Retirement Planning

If Trish adds $34,084 to her present RRSP balance of $54,000, she will have $88,084 in the account. If she makes no more contributions, that balance, growing at 3 per cent a year after inflation will become $159,100 in 20 years when Trish is 65. That sum, spent over 25 years to her age 90 would support an indexed and taxable payout of $9,140 a year. With the same 3 per cent inflation-adjusted return, the TFSA would rise to $93,975 and provide an annuitized income of $5,300 for 25 years.

Trish can expect to receive $13,370 from the Canada Pension Plan at age 65 and, at the same age, $6,942 a year from Old Age Security, both in 2017 dollars.

Adding up retirement income, Trish can expect $9,140 per year from her RRSP, $6,942 from OAS, $13,370 from CPP, and $5,300 from her TFSA. Rental income from the property she has retained would add $25,464 a year after the mortgage is paid off. Her total, pre-tax income at 65 adds up to $60,216 a year. After adjustment for no tax on TFSA payouts and a 15 per cent average tax rate on the balance, she would have about $4,300 a month for her expenses.

Her mortgage would be very small or paid if she accelerated payments. Loans would be paid. In all, debt elimination would save her $1,365 a month. Sale of property 2 would eliminate $645 monthly costs. The monthly $275 bus fare to work would be eliminated. Work clothing could be cut by $200 a month. Those savings would add up to $2,485 a month, reducing monthly allocations to $4,245. She would be within her budget to age 90, Moran estimates.

“If, as I hope, Trish has a long and fulfilling life, her investment income will allow her to maintain her present standard of living to 90,†Moran says. “After that, she’d have government pensions and rental property income.â€

(C) 2017 The Financial Post, Used by Permission