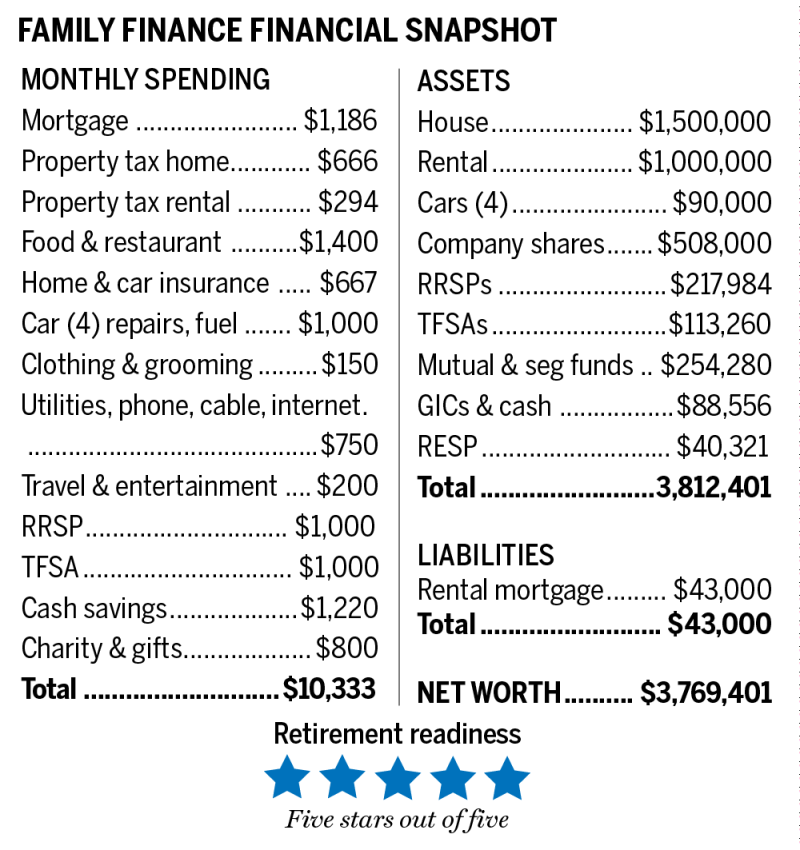

The couple’s assets add up to about $3.8 million and they have just $43,000 outstanding on a mortgage on the rental. They are meticulous in their records, cautious in their investments and thoughtful about their future. Their questions are focused on the composition of their retirement capital: $508,000 in shares in Sid’s employer and two future work pensions — $5,200 per month for Sid and $200 per month for Adele. They wonder what to do about the rental and how best to manage taxes liabilities on their pensions and financial assets.

Family Finance asked Derek Moran, head of Smarter Financial Planning Ltd. in Kelowna, B.C., to work with Sid and Adele.

An unprofitable rental

The first order of business is what to do with the $43,000 mortgage on the rental. They pay 2.87 per cent or $14,232 per year of which $1,287 is annual interest. This carrying charge is deductible and declining rapidly. It’s a modest sum, but the larger question is why keep the property?It generates $15,540 gross rent less $7,186 for property taxes, interest, insurance and utilities costs for net rental income of $8,354 per year. Their equity is $957,000 so their return on equity is a modest 0.87 per cent. That’s trivial and, given that they have never lived in it, any gains from sale will be fully taxable. It’s barely profitable. Best move — sell it, Moran advises.

Sale of the $1-million rental after five per cent selling and primping costs and the discharge of the $43,000 mortgage balance would leave $907,000. They paid $270,000 so they should have a capital gain of $637,000. The property is jointly owned, and at the present 50 per cent inclusion rate, the taxable gain is $318,500. That’s $159,250 to each. Sid’s income tax would increase from $20,646 without the sale to $92,669, a boost of $72,053 for the year.

Adele’s tax could rise from $7,659 now to $69,348, a $61,691 increase. She has $75,243 RRSP room and might use all of it to shelter her gain. Doing that would cut her tax by $33,572 to $35,776.

The proceeds of the sale would therefore be $907,000 less taxes of $72,053 and $35,776, respectively, net $799,171. They can get four per cent from strong dividend stocks, $32,000 per year, which is nearly four times the property’s current income.

Retirement income and spending

Looking ahead to expenses in retirement, present spending of $10,333 per month will drop when $3,220 monthly savings and the $1,186 monthly mortgage and $294 rental property tax are removed. That leaves $5,633 core spending to be supported.Sid can expect $5,200 monthly pension from his company, Adele $200 per month from her employer. Neither is bridged or indexed. When Sid retires, he should receive $14,445 per year from CPP in 2021 dollars, and Adele $10,834 from CPP at her age 65. Each will receive full Old Age Security, currently $7,707 per year.

Their TFSAs have a present balance of $113,260 composed of contributions and appreciation. They have $45,000 of unused contribution room. They can use their cash for additions. If they continue to work for two more years and add $6,000 each per year and the sum grows at three per cent per year after inflation, their TFSAs will rise to $192,988 on the brink of retirement. That sum will support payout of $9,766 per year to Adele’s age 90.

Their RRSPs total $217,984. Sid just added $13,600 to maximize his RRSP for 2021. If Adele adds her $75,243 to offset tax from the house sale, the total would be $306,827. If they work two more years and add $13,600 per year, then with two years growth at three per cent after inflation, will become $353,950 at retirement.

This sum could support a taxable flow of income indexed to inflation of $17,910 per year to Adele’s age 90. Withdrawals can wait to each partner’s age 71, to allow distributions to grow and offset declining purchasing power of their employment pensions.

Sid has $508,000 in taxable company shares. Their cost is $248,000 and their capital appreciation $260,000. They receive $12,022 per year in dividends from those shares. They can cash out and diversify, but that would best be done when their incomes have declined in retirement, reducing tax and potential OAS clawback exposure, Moran explains. This flow can start in two years.

The couple also has $188,823 of mutual funds and $65,456 of segregated funds. Seg funds guarantee a return of 80 per cent of capital if held for a decade. The combined sum, including company shares is $762,279. If this money is spent over 30 years from Adele’s age 60 to her age 90, it would support a further $36,570 total per year.

Taxes to pay

Before either partner is 65, they would have annual retirement income of $62,400 from Sid’s pension and $2,400 from Adele’s pension, $17,910 from RRSPs, $9,766 from TFSAs, and taxable income of $36,570. That’s a total of $129,046. Assuming splits of eligible income and 17 per cent average tax, with TFSA income excluded, then returned to cash flow, they would have $9,064 per month to spend.When Sid is 65, their income would rise by his $7,707 OAS and $14,445 CPP to $151,198. With TFSA cash flow removed, eligible incomes split and average tax of 19 per cent, then with TFSA cash flow restored, they would have $10,360 per month to spend.

Finally, when both partners are 65, family income would rise with Adele’s $10,834 CPP and her $7,707 OAS to $169,739. With a split of eligible incomes and removal of TFSA cash flow, after 20 per cent average tax and return of TFSA cash flow, they would have $11,480 to spend per month.

The OAS clawback, which starts to cut OAS when total income not including TFSA payouts reaches $79,845 and takes 15 per cent thereafter until all OAS is eliminated at about $129,750, will reduce the couple’s income each by the modest sum of $20 per year when both partners are 65.

Retirement stars: 5**** out of 5

Financial Post

( C) 2022 The Financial Post, Used by Permission