Commuting her pension could let this Ottawa civil servant have her cake and eat it, too. But is it worth the risk?

This dish is costly: annuities sold by profit-seeking insurance companies are not cheap, expert says

Lucille wants to retire next year, at age 49, and she is considering taking the commuted value of her pension.

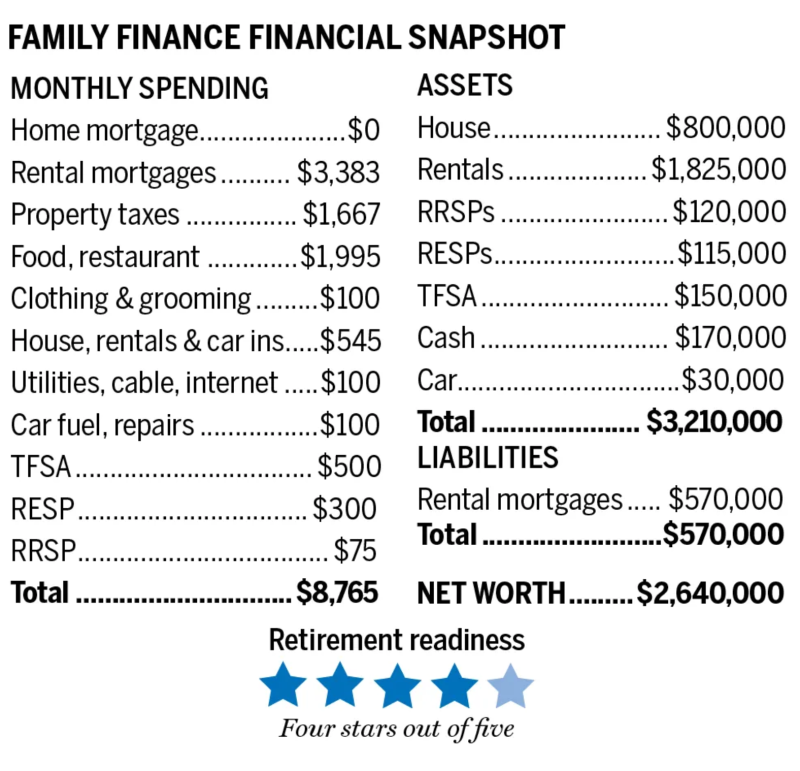

In Ottawa, a woman we’ll call Lucille, 48, works for the federal government. She has three children, all in their teens with adequate RESPs, a house worth $800,000, three rentals with an estimated total value of $1,825,000 and $570,000 of debt for the rentals.

Lucille wants to retire next year, at age 49, and she is considering taking the commuted value of her pension. That is the amount of money needed to generate expected pension income, which would be $48,000 per year at age 55, the earliest year she can start receiving income. With interest rates still low, it takes a lot of money to generate promised pension income. Thus it is a good time to be thinking over whether to cash out and take the commuted value. Lucille earns $116,000 per year and has $49,217 net rental income. After her average tax rate, 36.39 per cent, reflecting $60,043 tax, she has $105,174 income per year or $8,765 per month.

The commuted value of Lucille’s federal pension stands at $852,000 for two decades of work. She would invest it for what she thinks would be a higher return than the usual high single-digit-returns federal pensions generate. The rules of the process are that she would have to accept $342,000 locked into a retirement account, a LIRA, and walk away with about $510,000 of taxable cash. Tax would take about half of that sum, leaving her with about $255,000 for her own investments.

Family Finance asked Derek Moran, head of Smarter Financial Planning Ltd. in Kelowna, B.C., to work with Lucille.

Comparing pensions

Lucille has achieved a low double-digit return on her savings and is an impressive investor. However, beating a fully indexed federal pension is not just about returns. A defined-benefit pension is ageless. The beneficiary cannot outlive it. It is bulletproof in the sense that it is diversified far beyond what an individual can achieve and guaranteed not to lose value to any level of inflation. The downside is that the capital in any DB pension does not belong to the beneficiary. It belongs to the Government of Canada in this case.The difference between leaving the DB pension and taking the money is whether she needs the potentially higher return she might earn on the commuted value, with the understanding that the return could be lower as well. The essence of the difference between a government DB pension and a private investment is certainty. No stock market flop can depreciate the Government of Canada Public Service pension plan.

What’s more, the payouts are indexed, so if inflation soars, retirees are protected. However, if Lucille takes the commuted value, the money is hers to use for collateral for loans or to transfer by will to family or charities. Moreover, her own money from commutation could be used to buy a life insurance annuity which could run until her death even if she lives to 100 or more. This is a way to have her cake — control of at least some of her assets — and to eat it. But this dish is costly: annuities sold by profit-seeking insurance companies are not cheap.

Matching returns

Taking the commuted value turns out to be a life or death decision, in part. If she lives to age 90, she would have to achieve an average annual return of eight per cent after inflation but before tax to beat the DB pension, Moran estimates. Giving up her federal DB pension could cut other benefits such as dental and medical available in public service of Canada pensions.Lucille has present net worth of $2.64 million apart from her pension. After deducting mortgage capital repayment from rentals, her carrying cost is less than one per cent. Her largest investment commitment is to three rentals, all efficient investments. The $1,825,000 property value of the rentals less the $570,000 of mortgage debt leaves $1,255,000 equity. After taxes, condo fees, interest only on the mortgages, maintenance and accounting, she has net rent of $49,217. The rent is taxed as ordinary income at a marginal rate of 50.23 per cent in her bracket, but she might pay just 35.87 per cent in her tax bracket on Canadian stocks after application of the dividend tax credit. That makes stocks more efficient in tax terms and much less trouble in terms of maintenance, breakage, or non payment of rent by tenants, Moran notes.

Estimating retirement income

Before age 55 and the start of her DB pension, Lucille’s RRSP would provide $4,976 per year. Her TFSA would add $6,220 per year, taxable investment income $19,050 per year, and net rents $49,217 per year. That is a total of $79,463. After 20 per cent average tax, she would have income of $5,297 per month. That is short of present expenses less savings. Some part time work would be needed.From 55 to 65, she could add her $48,000 pension to boost income to $127,463. After 25 per cent average tax, her income would be $95,597 per year or $7,970 per month. That would cover present expenses without savings

From 65 onward, she could add $9,389 estimated Canada Pension Plan and $7,707 OAS income for total income of $144,560. She would pay 25 per cent average tax. The clawback which starts at $79,054 and taxes income at 15 per cent over that amount would take back all of her OAS. Her final income at 65 would be $108,420 per year or $9,035 per month, more than enough to cover her expenses.

The effect of an election to take the commuted value of her pension is to add uncertainty. The upper limit of her savings including commuted value could be a return of 10 per cent per year before tax. Or more. The lower limit could be total loss of her commuted pension.

Lucille can choose certainty and no control over much of her retirement savings or commute, pay hefty tax, and try to beat the returns of the federal indexed defined benefit pension. She might, but there are shocks to the best laid plans. In a market meltdown, she might need strong nerves. If she keeps the DB pension, she could yawn and go back to whatever she likes to do.

4 Retirement Stars **** out of 5

Financial Post

( C) 2022 The Financial Post, Used by Permission