Recent Immigrants bring Foreign Pensions but Worry how to Build Retirement Security in Canada

Andrew Allentuck

Situation: In their 40s, a couple who emigrated to Canada wants to know if they can pay for kids’ educations, then retire in their mid-60s

Solution: Add up resources, cut insurance cost, work out financing for university, annuitize retirement savings

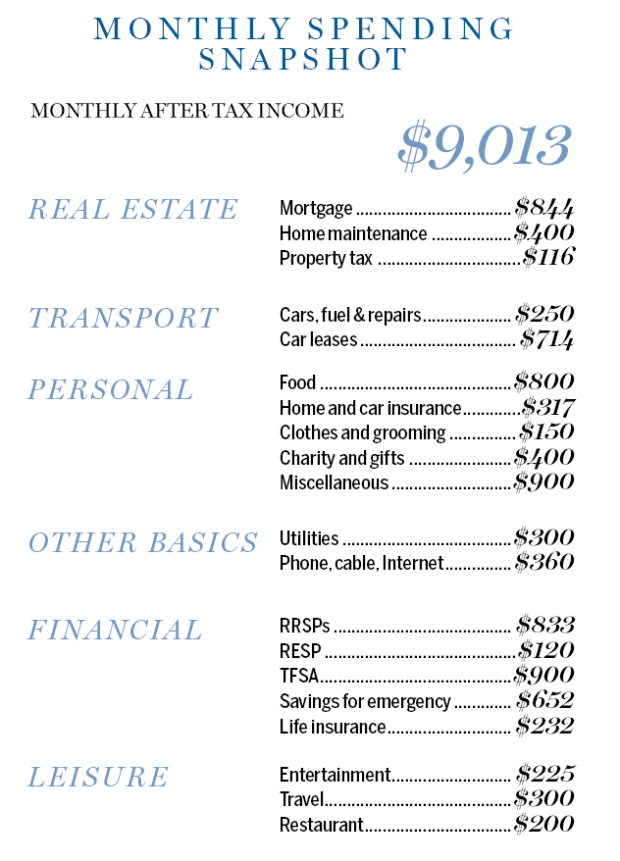

In Alberta, a couple we’ll call Burt, 48, and Ethel, 45, have three children — twins age 14 and a son just edging into his teen years. New Canadians, they arrived in 2008 with the kids, got jobs in a large health care organization, and brought entitlements to foreign pensions when they retire. They bring home $9,013 a month from two jobs that pay, in total, about $170,000 a year.

It seems a simple situation: raise the kids and then retire on pensions, including transferred credits from former foreign employment, Canada Pension Plan and partial Old Age Security benefits. Their concern as relatively new residents is to build security in a financial system that remains unfamiliar.

“What will our retirement look like?†Burt asks, reflecting a degree of bewilderment about the alphabet soup of RRSPs, RRIFs, TFSAs and many other abbreviated plans. “What do we have to do to build security? â€

Family Finance asked Derek Moran, head of Smarter Financial Planning Ltd. in Kelowna, B.C., to work with Burt and Ethel. “If they can use their cash flow more efficiently to reduce taxes and cut borrowing costs on their $325,000 of liabilities (and) invest their financial assets more effectively, they should be fine,†he says.

To start with, Moran outlines four things they can do right now:

Dip into $154,500 of cash paying one per cent to pay off an $11,000 line of credit that costs four per cent a year.

2. Beef up RRSPs. Burt has $16,800 of contribution room. He can use $13,140 of cash to top up current monthly contributions. He will get a 36 per cent tax refund — $4,730 based on his taxable income of $98,000 a year. Ethel has $47,730 of unused RRSP space. Her income, though fluctuating, has recently been about $70,000 a year. If she contributes $12,300, she can get a refund of about $4,000, Moran estimates. These catch ups total $25,440.

3. Prepay 20 per cent of their original $360,000 mortgage without penalty, as their bank allows. That’s $72,000. That will reduce the present mortgage balance of $320,000 to $248,000 and reduce amortization from 20 years to 14 years, 8 months, saving them $64,420 of interest. In this plan, when the mortgage is paid off, Burt and Ethel will be 62 and 59.

4. Reserve remaining savings of $46,060 to add to RRSPs over time, pay down the remaining mortgage under the 20 per cent annual penalty-free prepayment or to add to their present $10,500 TFSA balances. They have a total of $71,500 of available TFSA space. All are good choices, Moran says.

If couple wants to retire at 55, they’ll have to stick with their same old boring jobs

Why this couple should forget about retiring early and focus on paying for their kids’ educations instead

Cutting costs

Burt and Ethel have been generous to the financial services industry. They bought mortgage life insurance with a disability feature sufficient to cover the cost of the mortgage. The cost of this coverage is $232 a month, or $2,784 a year. Mortgage life covers the exposure of the lender should the borrowers be unable to pay, but there is usually no residue for family needs. An independent life insurance agent could provide $500,000 coverage on a 10-year level term policy for perhaps $900 to $1,200 a year, the exact rate depending on policy features. In a decade, the mortgage will be paid down or paid off entirely, depending on how Burt and Ethel use savings and tax refunds, and the kids will be close to finishing their university educations. In any event, they already have substantial life coverage through their job group plans.

Educating the Kids

The three children have Registered Education Savings Plans with a present balance of $25,000. Burt and Ethel add $120 a month but could raise the sum to $208 per child to qualify for the maximum Canada Education Savings Grant top-up of the lesser of 20 per cent of sums contributed or $500. If they raise contributions to $625 a month, then at three per cent annual growth after inflation, they will have $56,220, including CESG credits, in three years when their twins are 17. The CESG stops then, so they can then cut contributions to $208 a month for the youngest child who will have two more years of CESG eligibility. That child will have another $6,000 of contributions and CESG top-ups plus growth, making the notional account about $63,000. That sum can be cut into thirds so that each child has $21,000 for university tuition and books. The kids could get summer jobs to help with tuition, Moran says.

Retirement Plans

Looking ahead to retirement at a tentative age of 65, the couple should be able to generate about $10,000 of RRSP annual space to add to their present $523,912 of RRSP balances, most of which were transferred in from tax-deferred accounts from employment prior to immigration to Canada. If they fill this space, plus the catch-ups of $25,440, and if the sums grow at three per cent a year after inflation, their RRSPs will become $1,132,000 in 17 years when Burt is about to turn 65. If they can sustain the same three per cent after inflation growth rate, this capital could support annual payouts of $58,600 in 2016 dollars until Ethel is 90.

Burt can expect a pension from his present employer of $41,450 at 65. They will also have a foreign pension transferrable to Canada that will be worth as much as $20,000 a year by the time Burt retires. Their CPP contributions based on 26 years of total work for Burt and 23 for Ethel should give 65 per cent of the present $13,110 maximum benefit, or $9,950. Ethel’s CPP pension is less certain, since she works on renewable contracts. Assuming she maintains her employment, she would have a benefit of $8,300 if she retires at the same time as Burt.

Their TFSAs, with a current balance of $10,500 and present contributions of $11,000 total a year could grow in 17 years to Burt’s age 65 to $283,000 with three per cent growth after inflation, and support payouts of $13,231 a year for 33 years to Ethel’s age 95.

Burt and Ethel will have 25 and 18 years, respectively, of the 40 years needed to qualify for OAS. Using the 2016 OAS base payment, $6,846, at age 65 Burt would get $4,243 a year and Ethel $4,792 a year, assuming the new government returns the OAS start age to 65.

Adding up their pension components, they would have RRSP income of $58,600, foreign pension income of $20,000, a Canadian company pension of $41,450, combined CPP benefits of $18,250 and combined OAS benefits of $9,035. TFSA payments would add $13,231. Their total retirement income would then be $160,566 before tax. TFSA payouts included in the sum would not be considered income and thus not taxable, and would leave their taxable income below the OAS clawback trigger point of about $73,000 per person. If the couple splits pension income, they would pay average income tax in Alberta of 18 per cent using 2015 rates and thus have disposable income of $10,970 a month, more than enough to cover their present allocations of $6,054 a month, after savings for kids and retirement end, Moran says.

(C) 2016 The Financial Post, Used by Permission